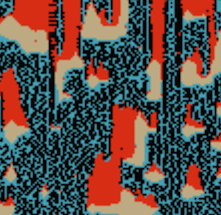

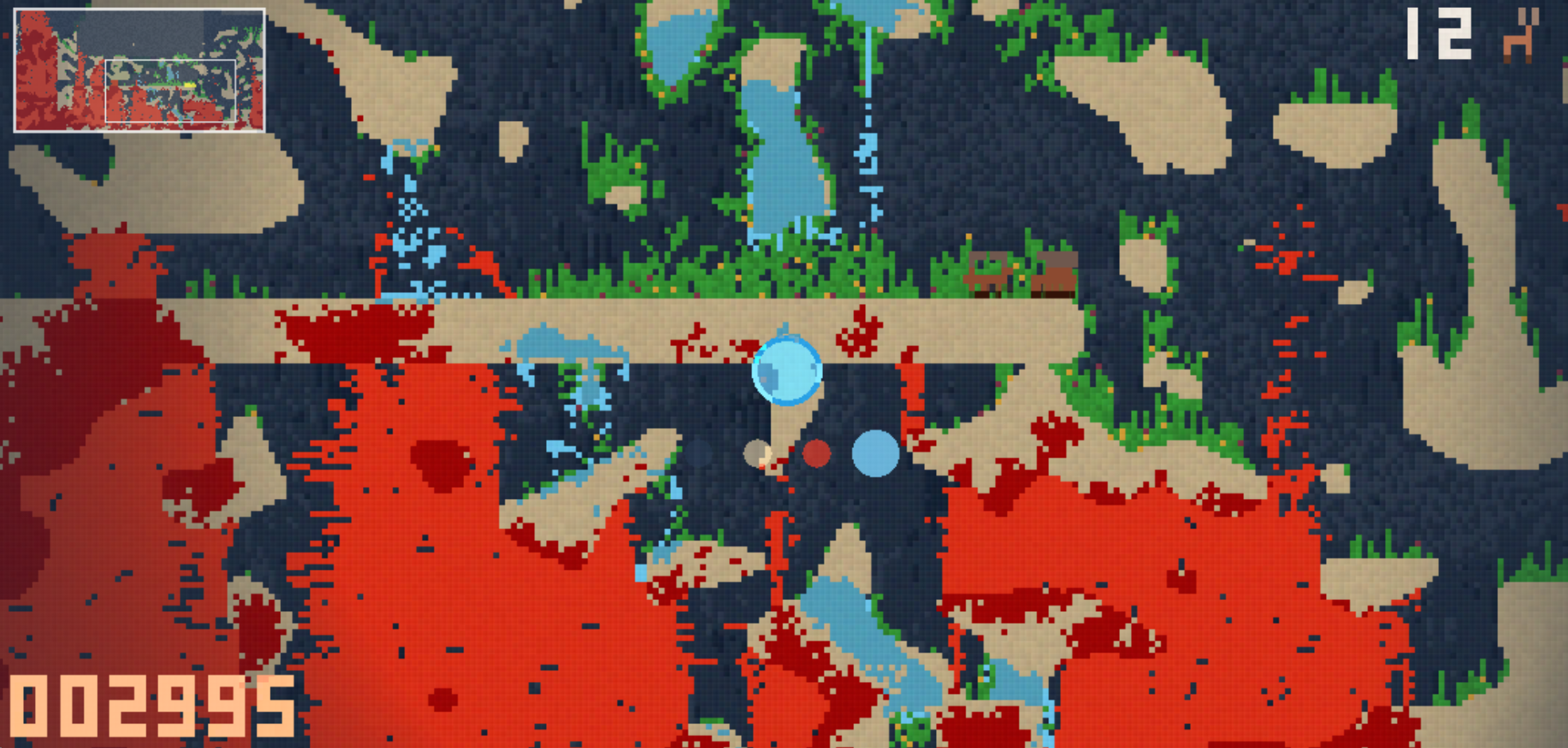

Last week I finished my JS13K game called "IBEX", an apocalyptic game where you have to help some wild ibex to escape from the inferno.

IBEX received the 16th place (out of 129 games) from the js13kgames jury.

This article is a technical post-mortem about the development of this game in JavaScript / WebGL and how the world is just ruled with cellular automata and computed efficiently in a GLSL shader.

Cellular automata ruled world

A Cellular Automaton (plurial Cellular Automata) is an automaton (in other words, a state machine) based on a grid (an array) of cells. It has been discovered years ago and popularized by Stephen Wolfram in his interesting book A new Kind of Science.

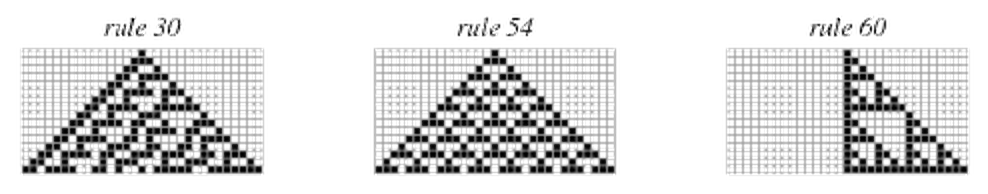

The simplest possible cellular automaton is the one where, at each generation, the cell value is determined from the previous and the 2 adjacent cells (left and right) value and where the value can only be 0 or 1 (white or black / true or false). The way the cell value is determined is through a set of rules.

In an elementary cellular automaton, there is a total of 8 rules, which means 256 possible cellular automata.

2D cellular automaton

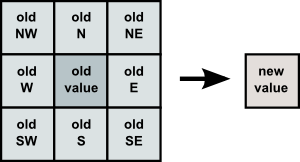

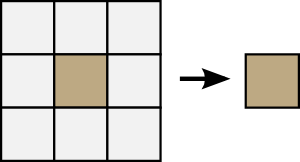

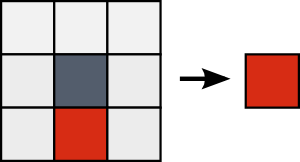

The kind of Cellular Automaton I focused on for my game is 2D cellular automaton: At each generation, the cell value is determined from the previous value and the 8 adjacent cells using a finite set of rules.

It is important to understand that these rules are applied in parallel for all cells of the world.

A 2D cellular automaton rule:

What I've found is that the WebGL and the GLSL language works well to implement a cellular automaton.

The GLSL paradigm is what I like to call functional rendering:

It is, to simplify, a function (x,y) => (r,g,b,a):

You fundamentally have to implement this function which gives a color for a given viewport position,

and you implement it in a dedicated language which compiles to the GPU.

So we can implement a 2D cellular automaton where each cell is a real (x,y) position in the Texture and where the (r,g,b,a) color is used to encode your possible cell states, and that's a lot of possible encoding!

In my game, i've chosen to only use the "r" component to implement the cell state.

But imagine all the possibilities of encoding more data per cell (like the velocity, the amount of particle in the cells,...).

Here is a boilerplate of making a Cellular Automaton in GLSL:

uniform sampler2D state; // the previous world state texture.

uniform vec2 size; // The world size (state texture width and height)

/*

The decode / encode functions provide an example of encoding

an integer state in the "r" component over possible 16 values.

You can definitely implement your own. Also "int" could be something more complex

*/

int decode (vec4 color) {

return int(floor(.5 + 16.0 * texture2D(state, uv).r));

}

vec4 encode (int value) {

return vec4(float(r) / 16.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

}

/*

get(x,y) is doing a lookup in the state texture to get the (previous) state value of a position.

*/

int get (int x, int y) {

vec2 uv = (gl_FragCoord.xy + vec2(x, y)) / size;

return (uv.x < 0.0 || uv.x >= 1.0 || uv.y < 0.0 || uv.y >= 1.0) ? 0 :

decode(texture2D(state, uv).r);

}

void main () {

// We get all neighbors cell values from previous state

int NW = get(-1, 1);

int NN = get( 0, 1);

int NE = get( 1, 1);

int WW = get(-1, 0);

int CC = get( 0, 0);

int EE = get( 1, 0);

int SW = get(-1,-1);

int SS = get( 0,-1);

int SE = get( 1,-1);

int r; // r (for result) is the new cell value.

////////////////////////////

// NOW HERE IS THE COOL PART

// where you implement all your rules (from the 9 state values)

// and give a value to r.

////////////////////////////

gl_FragColor = encode(r);

}

The complete game rules are all implemented in a GLSL fragment shader: logic.frag. It is important to understand that this fragment shader takes in input the previous world state (as an uniform texture) and computes a new state by applying the rules.

On the JavaScript side, you need to give an initial state to the texture (so you need to also encode data the same way it is done in the shader). Alternatively you can also make a shader to do this job (generating the terrain can be intense to do in JavaScript, like it is the case for my game...).

Also if you want to query the world from JavaScript,

(e.g. you want to do physics or collision detection like it is also the case for my game),

you need to use gl.readPixels and then decode data in JavaScript.

I'll explain this a bit later in another article. Let's now go back to the Cellular Automaton used in IBEX.

The elements

The game theme was "Four Elements: Water, Air, Earth, Fire", so I've used these 4 elements as primary elements of the cellular automaton.

Each elements also have secondary elements that can be created from each other interactions: Source, Volcano, Grass, WindLeft, WindRight.

- The Volcano is lava growing in the Earth. It creates Fire (when there is Air).

- The Source is water infiltrating in the Earth. It drops Water (when there is Air).

- The Grass (or Forest) grows on Earth with Water. It is a speed bonus for ibex but it propagates fire very fast. It also stop the water from flowing.

- The Wind (left or right wind) is created randomly in Air. It have effects on Water and Fire propagation and also on ibex speed.

Some constants...

// Elements

int A = 0; // Air

int E = 1; // Earth

int F = 2; // Fire

int W = 3; // Water

int V = 4; // Volcano

int S = 5; // Source

int Al = 6; // Air Left (wind)

int Ar = 7; // Air Right (wind)

int G = 8; // Grass (forest)

To summary, there is 9 possible elements, and rules are determined from the 9 previous cells: This makes a LOT of possible rules. However, the rules involved here remain simple and with just a few rules.

That is the big thing about cellular automata: very simple rules produce an incredible variety of results.

In general, we can classify my game rules into 2 kind of rules: "interaction" rules and "propagation" rules. The first kind describes how two (or more!) elements interact each other. The second kind describes the way an element evolve. Some rules will also mix them both.

Some simple "propagation rule"

Earth stays: an Earth is returned if there was an Earth before.

Water falls in Air: a Water is created if there was a Water on top.

Fire grows in Air: a Fire is created if there was a Fire on bottom.

These rules produce very elementary result, we will now see how we can improve them.

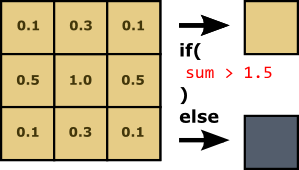

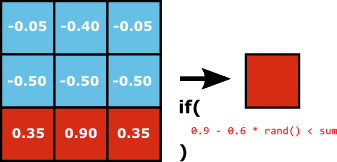

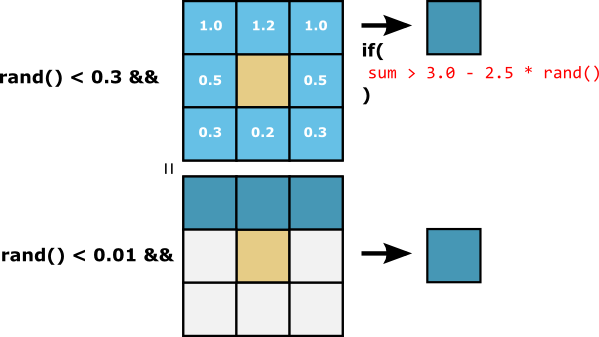

Weights in rules

More powerful rules can also be reached by using weights: you can affect a weight for each neighbor cell to give more or less importance to them.

Let's take a look at a simple example:

N.B.: only the "sum" is considered in the rule: if an element matches, we sum the weight of the cell, otherwise "zero".

This example is actually a weighted version of the cave rule you can find here:

Randomness in rules

Combine Randomness and Weights and you get a very powerful simulation.

To avoid seeing some (well known) patterns in the simulation I added some randomness in my rules. With randomness, the results are incredibly powerful.

In the following video, notice how cool the fire propagation can result by varying the propagation randomness factor.

The code:

#define AnyADJ(e) (NW==e||SE==e||NE==e||SW==e||NN==e||SS==e||EE==e||WW==e)

// ^^^^^^^^ MACRO !

if (

CC == G &&

RAND < firePropagation &&

( AnyADJ(F) || AnyADJ(V) )) {

r = F;

}

Randomness in GLSL ???

GLSL is fully stateless and there is NO WAY to have a random() function in the GPU.

The trick to do randomness in GLSL is by invoking some math black magic:

float rand(vec2 co){

return fract(sin(dot(co.xy ,vec2(12.9898,78.233))) * 43758.5453);

}

rand is a popular

function which returns a pseudo-random value (from 0.0 to 1.0) for a given position.

My personal black magic was to define a convenient macro to have a "RAND" word which would get me a new random number.

#define RAND (S_=vec2(rand(S_), rand(S_+9.))).x

S_ is a seed which is accumulated when calling this RAND.

Because this macro will be inlined in the code, S_ must be defined in a local variable

(so in summary, RAND is doing local side-effect).

vec2 p = gl_FragCoord.xy;

vec2 S_ = p + 0.001 * time;

Note that the current pixel position itself AND the time are both used for initializing the seed. It produces variable randomness over time and for each pixel.

Let's now see other examples where randomness can be very powerful.

The Water and Fire interactions

Fire grows and diverges:

- the "left" and the "right" columns in this rule allows divergence in the way fire grows: Instead of growing straight up, the fire can also move a bit left or a bit right. A lower weight for these side columns make the fire diverge a bit less than a "triangle" propagation.

Here is the GLSL code:

// Fire grow / Fire + Water

if (

-0.05 * float(NW==W) + -0.40 * float(NN==W) + -0.05 * float(NE==W) + // If water drop...

-0.50 * float(WW==W) + -0.50 * float(CC==W) + -0.50 * float(EE==W) + // ...or water nearby.

0.35 * float(SW==F) + 0.90 * float(SS==F) + 0.35 * float(SE==F) // Fire will move up and expand a bit.

>= 0.9 - 0.6 * RAND // The sum of matched weights must be enough important, also with some randomness

) {

r = F;

}

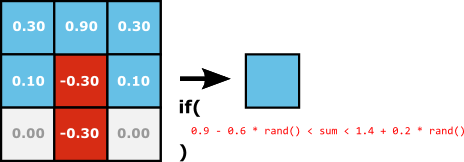

Water falls, diverges and creates holes:

- Same as the fire rule, we also have divergence in the water.

- However there is one more important thing in the rule: thanks to the double inequality, Water is created only if there is not already too much Water: it results of creating Air between the Water particules. This make Water elements to be less compact than Fire elements, the water does not visually "expand" contrary to the fire.

- The randomness helps a lot here to give no visible patterns in this job.

Here are all rules which creates Water: in this rules you can also notice how the Water flows on Earth and how the occasional rain is implemented.

if (

// Water drop / Water + Fire

between(

0.3 * float(NW==W) + 0.9 * float(NN==W) + 0.3 * float(NE==W) +

0.1 * float(WW==W) + -0.3 * float(CC==F) + 0.1 * float(EE==W) +

-0.3 * float(SS==F)

,

0.9 - 0.6 * RAND,

1.4 + 0.3 * RAND

)

|| // Water flow on earth rules

!prevIsSolid &&

RAND < 0.98 &&

( (WW==W||NW==W) && SW==E || (EE==W||NE==W) && SE==E )

|| // Occasional rain

!prevIsSolid &&

p.y >= SZ.y-1.0 &&

rainRelativeTime < 100.0 &&

between(

p.x -

(rand(vec2(SD*0.7 + TI - rainRelativeTime)) * SZ.x) // Rain Start

,

0.0,

100.0 * rand(vec2(SD + TI - rainRelativeTime)) // Rain Length

)

|| // Source creates water

!prevIsSolid && (

0.9 * float(NW==S) + 1.0 * float(NN==S) + 0.9 * float(NE==S) +

0.7 * float(WW==S) + 0.7 * float(EE==S)

>= 1.0 - 0.3 * RAND

)

) {

r = W;

}

Source rules

The Source can be created in the Earth by two rules: Either there is enough water around, Or there is source on top.

Note the important usage of randomness.

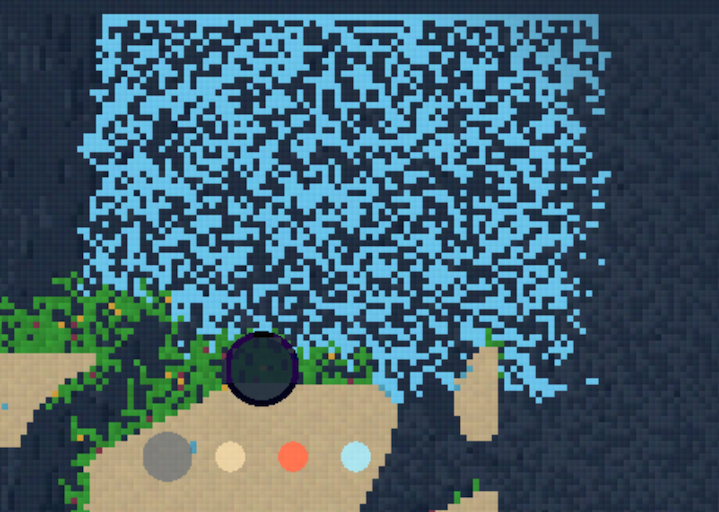

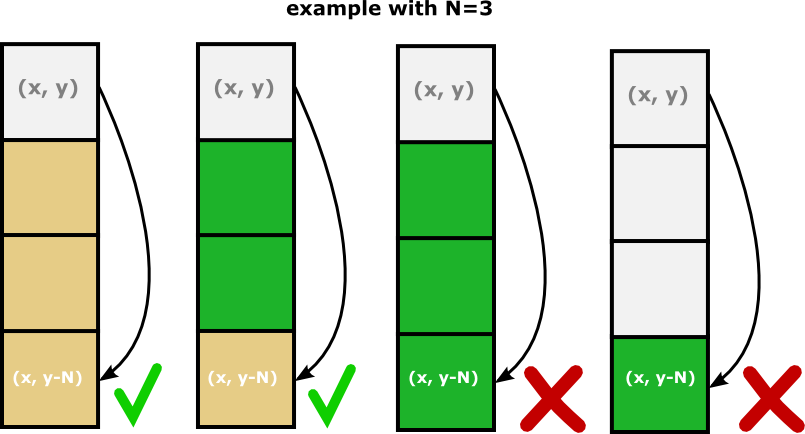

The grass propagation, Limiting the forest height

To finish, the grass needed a special extension to the so-far-used 2D cellular automaton, the grass cell value is not only being determined from the 8 adjacent cells:

To have more complex structure, the grass is determined

from the previous cell at position (x, y-N),

where x and y is the cell position and N is a variable value (random but constant per cell position).

In other word, a forest can grow if the cell at N step under it is not a forest.

This extra rule just adds a constraint on the max height that a forest can have.

Here is a demo showing the forest propagation randomness:

Drawing into the world

Drawing into the world is also done in GLSL: through uniforms.

Another alternative way to do that would have be to use gl.readPixels to extract it out in JavaScript,

to write into the Array and inject it back to the shader...

but this solution is not optimal because readPixels is blocking and costy (CPU time).

uniform bool draw; // if true, we must draw for this tick.

uniform ivec2 drawPosition; // The position of the drawing brush

uniform float drawRadius; // The radius of the drawing brush

uniform int drawObject; // The element to draw

void main (void) {

...

bool prevIsSolid = CC==E||CC==G||CC==V||CC==S;

if (draw) {

vec2 pos = floor(p);

if (distance(pos, vec2(drawPosition)) <= drawRadius) {

// Inside the brush disc

if (drawObject == W) {

// Draw Water

if (prevIsSolid && CC!=G) {

// Source is drawn instead if there was a solid cell

r = S;

}

else if (!prevIsSolid && mod(pos.x + pos.y, 2.0)==0.0) {

// We draw Water half of the time because Water is destroyed when surrounded by Water

r = W;

}

}

else if (drawObject == F) {

// Draw fire or volcano if solid cell.

r = prevIsSolid ? V : F;

}

else {

// Draw any other element

r = drawObject;

}

}

}

...

}

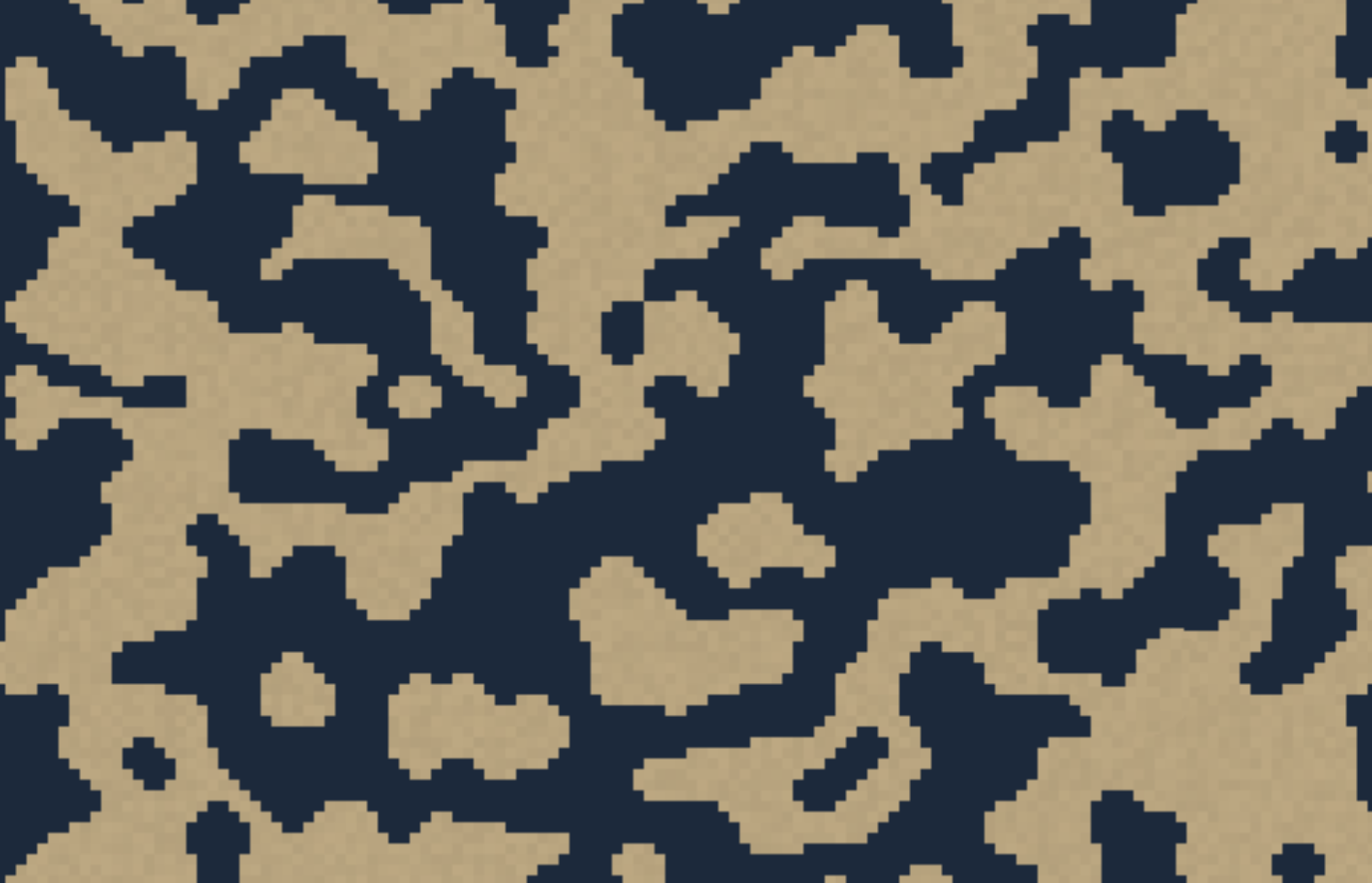

World generation is also a Cellular automaton!

The world is generated on the fly when the ibex progress to the right. This is done chunk by chunk.

More precisely, the world height is 256 pixels and a new part of the world is discovered each 128 pixels – In other words, the generation is divided into world chunks of

(128 x 256)pixels.

Each world chunk is generated using a cellular automaton (different from the simulation one).

As shown in a previous example, we can easily generate "cave like maps" from this technique. I've added to this a few improvments:

- The initial random conditions ensure that the bottom of the world is Earth and that the top of the world is Air. (that with gradients of randomness)

- Randomness has been added to the rules to make the terrain evolving a bit more (otherwise it creates stable but small caves).

- The number of generation step is set to 26. the randomness of the rules is decreasing through steps to produce stable results.

- In an attempt to create seamless maps, the initial random state for x=0 is set to the values of x=127 of the previous world chunk. (code here) It isn't perfect because you can still notice some edges.

- For more diversity in generated chunks, here are the parameters that can randomly vary:

- The amount of Earth (can create dense areas VS floating platform areas)

- The chance of Water Source in the Earth (will creates a lot of forest)

- The chance of Volcano in the Earth (dangerous world chunk)

More articles to come

Did you like this article?

I'll try to write more about these subjects:

- The "Pixels paradigm", Pixel as first class citizen: How to query and analyze the pixels world. How to do simple bitmap collision detection.

- The game rendering performed in a GLSL shader and all the graphics details I've spent hours on.

- things I've learned from WebGL, how to solve the bad approaches I've taken, and how I could have made a much more efficient game.

- what could have made this game even more interesting, and some ideas that was not reachable in a 2 weeks deadline.